In a religiously and ethnically diverse region such as Asean, there is a close connection between religious freedom and peace and security. Conversely, persecution and vioasealations of religious freedom raise the risk of conflict that can threaten national and regional security, a new study shows.

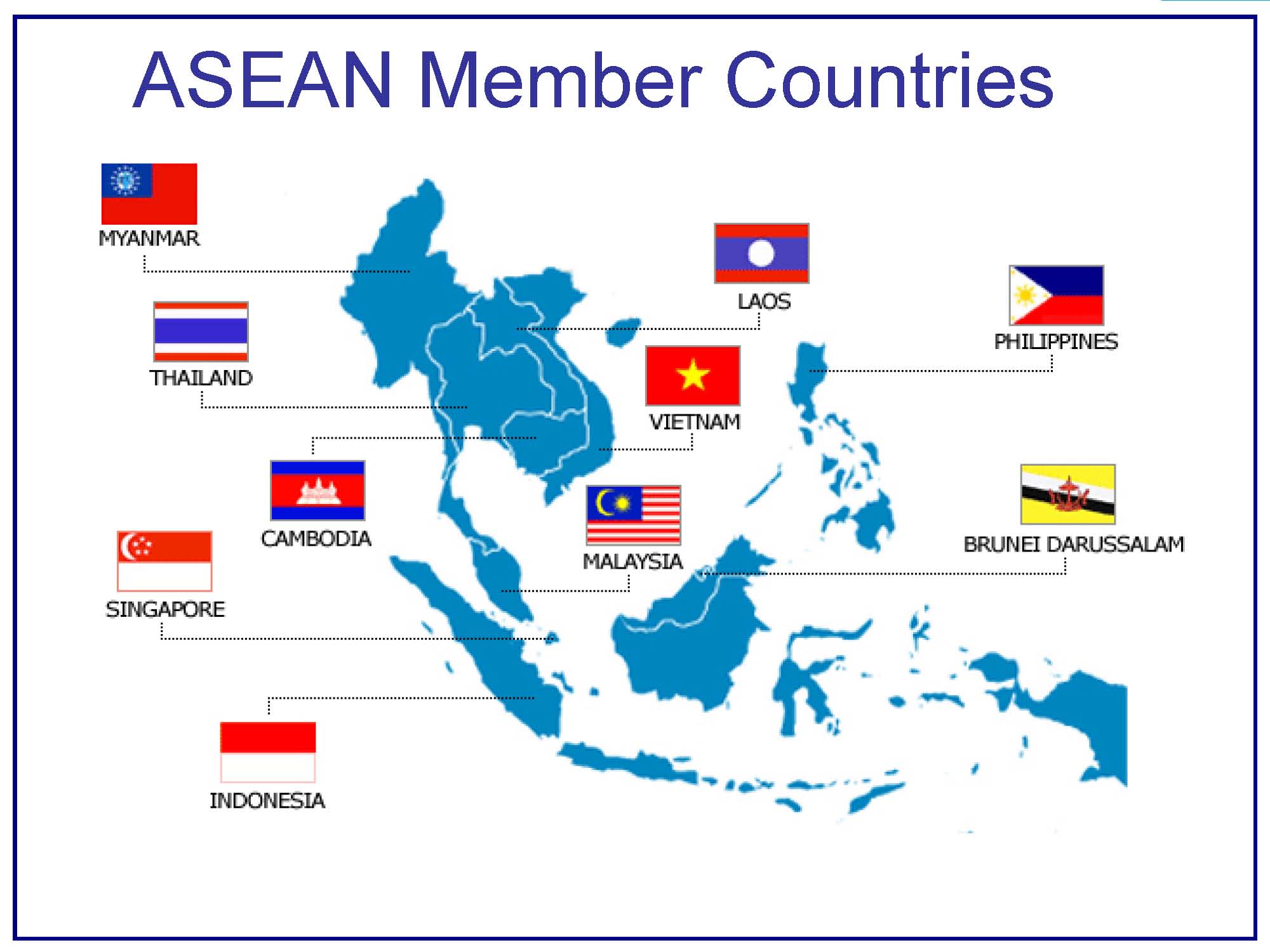

Religious conflict is “a conflict that will affect the entire society”, said Dr Jaclyn Neo of National University of Singapore, the lead author of “Keeping the Faith: A Study of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in Asean”. The report was based on research covering all 10 Asean member states by the Human Rights Resource Centre based on the Depot campus of the University of Indonesia in West Java.

Article 22 of the Asean Human Rights Declaration states that everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion and it ensures elimination of all forms of intolerance of hatred based on religion and belief. Those pledges adopted by all member states have been tested from time to time, most notably in Myanmar today.

Researchers across the region collected the data for the study based on secondary sources such as statements and publications by individual member states, international and regional organisations, think tanks and civil society groups. They found varying degrees of religious persecution in the region, with the exception of Singapore and Brunei, and signs of significant violent persecution in Myanmar, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Dr Neo said the most extensively documented violent religious persecution in Myanmar is of the Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state, which had shown a significant increase since 2012.

“Violations include lack of right to citizenship, restrictions on freedom of movement, obstacles to family development and exclusion from the local economy,” she said. “Reports from the country argue that the state should be held responsible for the religious conflict.”

In Malaysia, people who intend to renounce Islam face prosecution and detention, and local laws in Terengganu state even rule that apostasy is a capital crime. Shia Muslims also face detention in Malaysia and they fare no better in Indonesia, where there have been cases of fatal attacks against them in East Java. Shia Muslims in the country also face bans on the right to express their thoughts on Islam.

The report also documented significant religious conflicts between religious groups. In predominantly Buddhist Myanmar, conflicts between Buddhists and Muslims have been widely reported, whereas in Muslim-majority Malaysia and Indonesia, there were cases of oppression against the Christian minority.

“The politicisation of religion during local elections is a contributing factor to this conflict in Indonesia,” Dr Neo said.

In the Philippines, where the population is 80% Roman Catholic, conflict with the Muslim minority remains a serious issue, while in predominantly Buddhist Thailand, Muslims in the country’s far South have long complained of oppression.

“[The conflicts in the Philippines and Thailand] originated with separatist Muslim groups,” said Dr Neo. “But religion is only one factor and it is mixed with political, social and economic discontent.”

The Philippine government agreed on a peace accord with the Muslim secessionist movement in 2012 and it is gradually being put into place. Prospects for an end to Thailand’s southern strife seem extremely remote, however.

The country report from Vietnam showed improvements in the treatment of minority religious groups while reports from Laos and Cambodia showed a decreasing trend in reported incidents of religious persecution.

“The lack of reported of religious persecution in Cambodia is commendable,” Dr Neo said, adding that the trend could be attributed to the fact that the country is still concentrating on rebuilding following the destruction wrought by the Khmer Rouge regime.

In Singapore, there have been no significant reports of violent or non-violent religious persecution or religious conflict since 1964. The situation could be attributed to the state’s strong monopoly on power that has resulted in a general lack of political and civic space for dissent. The same conditions allow Brunei to claim no reported cases of religious conflict or persecution.

“The state has taken strong control of the position that religious conflict has no place in Brunei,” Dr Neo said. However, some serious concerns have arisen about the implementation of full shariah law in the sultanate.

Ong Keng Yong, a scholar from Singapore’s Rajaratnam School of International Studies, said the results of the study should be interpreted in the context of appreciation for Asean’s diversity as a regional grouping. Many changes have taken place in the area of human rights protection and promotion in the region, he said, and contrary to widely held perceptions, this shows that human rights remains a core issue in the bloc.

Ong said that Asean leaders for the past 10 years had made an effort to institutionalise the protection and promotion of human rights. The establishment of the Asean Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) is an example of that effort.

“We are still not perfect; we are still trying to navigate ourselves through these difficult areas,” said Ong, who was the Asean secretary-general from 2003-07. “Asean is a very, very diverse region and really different from other regions in the world. We must bear this in mind whenever we talk about Asean.”

Nina Hachigian, the United States Ambassador to Asean, agreed that the region has a remarkable diversity of religions and that every person should be entitled the universally accepted human rights which includes freedom of religion and freedom of speech.

“Those are the values that we work for with individual countries [in Asean] and with Asean as a whole,” she said.