When talking about the success of this model throughout its history one

must acknowledge the fact that it is not free of problems, weaknesses,

and failures, and this is the case for every political actor from the

greatest empires to the smallest political groups.

Hezbollah is a small organization fighting “Israel”, which is a regional

entity and project with unlimited international support. Therefore, it

needed material and financial assets, cadres, an incubating environment,

a logistical structure, a dynamic and charismatic leadership, and a

strategic geopolitical depth (national and supranational). How did

Hezbollah achieve this?

The dimensions of this success and its historical circumstances are

intertwined, but it is necessary to sort and disassemble them to get a

clearer picture.

Also, focusing on the elements of success and uniqueness does not

translate into ignoring the obstacles, challenges, and changes. Shedding

light on these elements contributes to enhancing our understanding of

their importance and their role in the party’s march, in a way that

encourages interaction with them in terms of reform, correction, and

care. Hence, their inclusion is not the result of complacency or vanity.

1- The founding generation gains experience: The first

generation of Hezbollah gained experience and expertise within Lebanese

and Palestinian political and military movements, during difficult times

of civil war and confronting the “Israeli” enemy.

They experienced challenges, problems, and failures that reinforced

their desire and need for changes and acquiring the necessary resources,

skills, and networks of influential interpersonal relationships.

A number of cadres belonging to the first generation had plenty of

experience in large parties such as the Amal movement, local Islamic

movements, mosque groups, and a few of them were part of non-Islamic

resistance forces (Fatah movement).

This generation experienced communist and nationalist ideas, argued with them, responded to them, and often competed with them.

This generation suffered the disappointments of the defeat of the

Nasserist project, the kidnapping of Imam Musa al-Sadr, the

assassination of Sayyed Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr in Iraq, the repeated

“Israeli” aggressive operations, and the expulsion of the Palestine

Liberation Organization from Jordan and then Lebanon.

All of these prompted the founders to try and think in a different way.

For example, from a military point of view, their collective experience

contributed to the planning and implementation of the most dangerous

military and security operations during the 1980s, which established a

solid foundation for the party's saga.

2- Taking inspiration from the Islamic Revolution and integrating with it.

The victory of the revolution in Iran transformed the broader Islamic

world. For the Shiites this was a historic opportunity to break out of

the state of oppression.

The Lebanese Shiites were the first to network with the victorious

revolution, especially since some of the cadres had built strong

personal relations with Iranian cadres opposed to the Shah’s regime and

provided them with assistance in Beirut, in addition to religious

relations with Iranian figures due to contacts through the Hawzas in

Najaf and Qom.

Thus, the benefits of the Islamic revolution reached Lebanon quickly.

The most prominent of these was the arrival of the training groups sent

by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps by order of Imam Khomeini to

the Bekaa Valley through Syria following the “Israeli” invasion in 1982.

To carry on and grow, this resistance required organizational frameworks

that gradually took shape until the structure of Hezbollah emerged.

The existence of this regional support for the resistance is

indispensable in light of the imbalance of power. The Iranian regional

political support and Iranian material resources (arms, training, and

money) enabled Hezbollah throughout the decades to focus on the conflict

with the “Israeli” enemy without needing to be constantly preoccupied

with securing support or searching for compromises with regional powers

in pursuit of protection.

The religious/ideological link between the party and the Wali al-Faqih

[guardian Islamic jurist] organized the party’s relationship with Iran

and facilitated an understanding between them. It allowed the latter to

look at the party from several perspectives, namely the Islamic

revolution, which is hostile to the American system of hegemony in the

Islamic field (specifically the resistance in Lebanon and Palestine) and

Iranian national security as well as preserving Shiism.

3- Solidifying the historical resistance framework of the Lebanese Shiites

Hezbollah engraved and reproduced the history of the Lebanese Shiites

from the angle of their role in resisting the Ottomans, the French, and

the Zionists.

Imam Khomeini’s fatwa for the delegation of the nine (they formed the

nucleus of establishing Hezbollah) on the duty to resist the “Israeli”

occupation with the available capabilities, no matter how modest, played

a pivotal role in activating the resistance project as a religious duty

first and foremost.

Thus, Hezbollah became a natural extension, compliment, and boost to the

experiences of the Shiite revolutionaries at the beginning of the

twentieth century and the positions of their great scholars such as

Sayyed Abdul Hussein Sharaf al-Din and Imam Musa al-Sadr. All these are

figures deeply enshrined in the conscience of the Shiite community,

especially Imam al-Sadr (the founder of the Lebanese resistance

regiments "Amal") due to the temporal rapprochement between its

experience and the birth of Hezbollah.

Therefore, loyalty to the resistance project is no longer loyalty to the

party, but to the sect's heroic role in defending the natural unity of

Syria and in the face of the “Israeli” occupation since the beginning of

its aggression against occupied Palestine.

4- Spreading power and confidence within an oppressed sect

The historical grievances and the structural marginalization of the

Lebanese Shiites, especially after the defeat of their revolution in

1920 (and they had been defeated before that in the second half of the

18th century in Mount Lebanon), contributed to their thirst for changing

their reality and the presence of a high revolutionary readiness that

was being nourished by the restoration of the revolutionary practices of

the Imams of Prophet Muhammad’s household (PBUH).

Hezbollah presented the resistance project under the title of

confronting occupation and hegemony to which the sectarian system is

affiliated. This would free the society from marginalization and

oppression - the world in the party’s ideology is divided between the

oppressed and the arrogant.

What helps the party perpetuate this narrative is its already strong presence among ordinary people born after the mid-1940s.

Hezbollah recalls this marginalization, which the society is actually

experiencing firsthand – once directly as Shiites and once as part of

the center’s marginalization of the parties in the north, the Bekaa, and

the south. These areas are inhabited by an Islamic majority, and this

made it easier for the party to communicate with various national groups

under the rubric of confronting deprivation and marginalization.

Accordingly, Hezbollah's success with resistance had multiple

dimensions, serving as a remedy for dissipated pride dating back nearly

two hundred years.

5- Filling the void in the shadow of a failed state

The civil war and the resulting settlement, which the party was not a

part of, led to the emergence of a weak state incapable of carrying out

many of its sovereign duties.

This allowed the party to carry the responsibility of the resistance and conduct social work for relief and development.

This state was not, in several stages, in agreement with the resistance

project. It was even hostile towards it at times, including the era of

Amin Gemayel and later Fouad Siniora’s destitute government.

However, it [Siniora’s government] was too weak to confront the resistance even with the help of external supporters.

This chronic state deficit that resulted in a lack of sovereignty

reinforced the popular legitimacy of the resistance and forced the party

to assume responsibilities that were not at the heart of its project,

especially with the deterioration of the economic situation in the past

two years.

6- Benefiting from the advantages of Lebanese Shiism, which

tested nationalist, leftist, patriotic, and Islamic currents and

produced a large number of intellectual and scholarly figures (Sheikh

Muhammad Jawad Mughniyeh, Sayyed Mohsen al-Amin, Sayyed Muhammad Hussein

Fadlallah, and Sheikh Muhammad Mahdi Shams al-Din, etc.).

It was historically characterized by a moderate tendency resulting from

the peculiarities of the highly diverse and complex Lebanese reality,

and later due to the many waves of migration towards Africa and the

West.

In recent decades, the Shiite community has also witnessed the

phenomenon of displacement to urban centers (Beirut, the southern Matn

coast, and Tyre) and integration into the contracting and trade sectors,

which had repercussions on their social class and political awareness.

Hezbollah had to work and grow within this type of complex Shiism, and

therefore, its relationship with the general Shiite environment is based

on a mixture of loyalty to it and negotiation at the same time.

This requires the party to be distinguished by social flexibility and

targeted communication for each circle of its incubating environments,

each of which has its own cultural, class, and regional characteristics

for the Shiites themselves.

The party gradually attracted elements and cadres from these circles,

which was reflected in an internal organizational vitality capable of

understanding the complexities of the Shiite scene, dealing with it, and

understanding its various internal sensitivities.

7- Maneuvering within the complexities of the Lebanese system

resulting from deep-rooted sectarianism, its exposure to external

interference, and its highly centralized financial-business economic

model, required Hezbollah to maintain a safe distance. The movement

positioned itself on the system’s external edge and approached it only

to the extent that was needed to protect the resistance from local

players with foreign ties to the United States and its allies.

Therefore, this complexity imposed on Hezbollah to weave broad

horizontal relations in the general political sphere (it had to develop

its political thought and initiatives to build a network of

cross-sectarian national alliances) and restricted vertical relations

within the political system.

However, the deterioration of the political system and its poles,

leading to the danger of the state’s disintegration, put the party in a

historical dilemma; it must work through the system itself to ward off

the danger of the state’s collapse (a concern that has grown in the

party’s awareness after the devastation that befell Syria and Iraq and

the accompanying disintegration of state structures) with apprehension

that engaging in regime change or reform would lead to an externally

backed civil war.

From the beginning, Hezbollah, in particular, had to be aware of the

external interference in Lebanon, its channels, borders, and goals, as

they represented an imminent threat to it.

Just like that, the party's local political choices could have

reinforced tension or appeasement with local and international forces.

It was not possible for the party to estimate the direction of the

policies of foreign powers (such as America, Saudi Arabia, and France)

in internal affairs and how to deal with them regardless of the

international and regional situations.

Therefore, the party has developed complex decision-making mechanisms

from its developing experience in Lebanese politics, which are

mechanisms that it can employ in other areas related to the resistance

and its regional role.

8- The rapid positioning within the Lebanese political arena of

conflict is crowded with competitors. Hezbollah came into existence amid

a heavy presence of political forces, armed and unarmed, most of which

have external relations. It had to expand its influence within all this

fierce competition.

In its

infancy, the party underwent several field tests and intense political

competition with major Lebanese forces rooted locally and forces with a

regional reach.

Then the party became vulnerable to severe political attacks from the

anti-resistance forces, especially after 2004. The burden of this

competition increased after Hezbollah confronted the leadership of a

national alliance with the so-called March 8 forces and the Free

Patriotic Movement.

Hezbollah's opponents receive extensive external support and are

distinguished by their presence in various cultural, media, and

political spheres in the form of parties, elites, platforms, the private

sector, and non-governmental organizations, which are entities closely

integrated with regional and international financial and political

networks hostile to the resistance.

Some of these adversaries play security roles that double their threat.

This reality produces constant pressures on the party, forcing it to

dedicate part of its resources and capabilities to the local political

sphere. It also makes it accumulate skills, frameworks, and criteria for

managing political competition in a way that guarantees it the local

and national stability necessary to avoid open internal conflicts that

distract it from its main mission.

9- Intellectual rivalry in a complex and open public sphere

resulting from the richness of the Lebanese political and intellectual

life, contrary to what is the case in most Arab countries.

The party had to present its Islamic thesis in a highly competitive

intellectual market where leftist, liberal, and nationalist currents

have deep roots and prominent thinkers in the region.

This is what the party quickly realized in its infancy and prompted it

to self-review the Islamic state and the Islamic revolution.

The party is

constantly confronting political and cultural arguments that are highly

critical of its political and cultural project (apart from a fierce

information war) that prompted a number of its elites and institutions

to engage in this “market” and root the party’s proposals on issues such

as Wilayat al-Faqih, the homeland, the Lebanese system, multiple

identities, the legitimacy of the resistance weapon, American hegemony,

and social justice.

As a result, despite the party’s intense preoccupation with the issue of

resistance and its requirements from the tactical cultural discourse,

it finds itself obliged to engage in many discussions and develop its

intellectual, research, and scientific institutions and cadres – a

challenge still facing the party.

10- The ability to transform geography into its environment.

The geographical contact of the Shiite communities in Lebanon with

occupied Palestine in southern Lebanon and the western Bekaa made this

environment targeted by “Israeli” aggression and under constant and

imminent threat.

Thus, the party gained enormous influence and wide embrace within these

communities through the success of its experiment in resistance,

liberation, and deterrence.

This contact and the success of the party produced what is called the

incubating environment, which is the most important element in the

success of the resistance’s experiences.

The party has succeeded in completely assimilating into this

environment, including its fighters, cadres, leadership, voters, and

supporters.

This contact gave rise to a historical Shiite awareness of the

Palestinian issue resulting from the historical personal and commercial

ties between the Shiite and Palestinian communities and then Shiite

engagement with Palestinian organizations and the residents of

Palestinian camps after the 1948 Nakba.

On the other hand, this contact with “Israeli” aggression had a

significant impact on Shiite urbanization and migration, as the occupied

areas witnessed extensive Shiite migration to Africa and North America,

and internally to coastal cities, specifically Tyre and Beirut.

This migration was a decisive element in the social and political rise

of the Shiites, as well as giving Hezbollah popular incubators in vital

areas and providing it with necessary human and material resources.

11- The participatory nature of the relationship with Iran:

The two sides dealt from the beginning on the basis that Iran’s role is

to support the party’s decisions that it takes in accordance with the

data of the Lebanese reality, especially since the Iranian state was

preoccupied with major internal and external challenges.

Therefore, the Wali al-Faqih used to grant legitimacy to the act,

provided that the party takes the necessary decisions. Later, Hezbollah

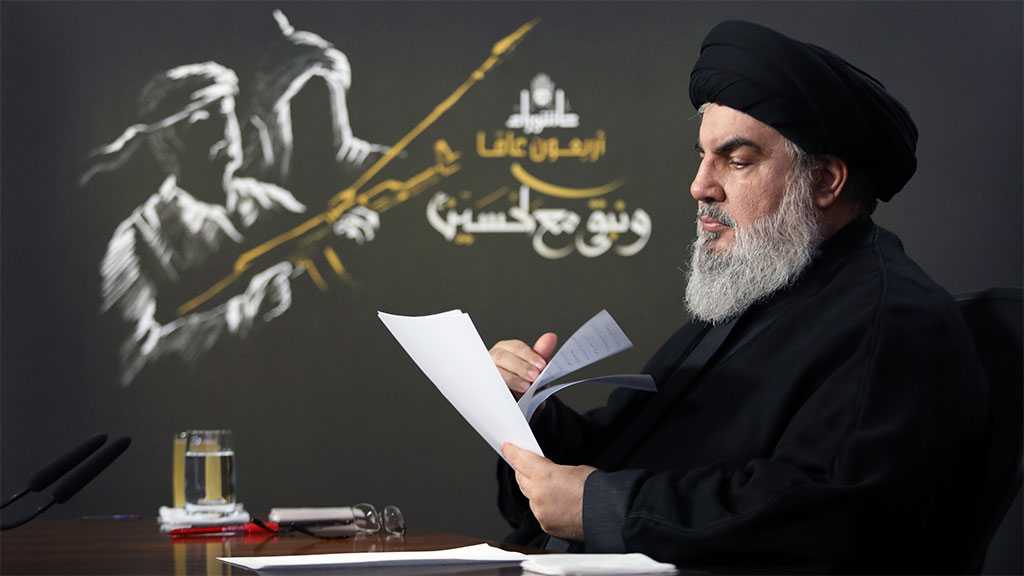

was able, due to its successes and the role of its Secretary General

Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, to become a partner in the Iranian regional

decision-making process, especially in the files related to the

resistance project.

This partnership is reinforced by the influence of the Revolutionary

Guards within the Iranian national security establishment, and the broad

respect for the party's experience among the Iranian people is a lever

for this partnership.

The Iranians were keen from the beginning to play the role of an

assistant to Hezbollah, which is why the decision was to send trainers

instead of fighters to Lebanon after the “Israeli” invasion.

This independence is reinforced by the theory of Wilayat al-Faqih itself, which recognizes local and national specificities.

With the Wali al-Faqih having the authority to command in all

administrative affairs, but according to wisdom, justice, and the

ability to understand interests and conditions of time, which are among

the obligatory attributes of the Wali al-Faqih, he realizes that every

local and national society has deep peculiarities that its people tell

about.

Therefore, the Wali often leaves the party to determine the interests after he adjusts their terms.

This partnership had a direct reflection on Hezbollah's regional

influence, as the Iranians realize that the party's Arab identity, along

with what it has accumulated in the Arab conscience, makes it, among

other arenas and files, a major player in managing the resistance

project.

12- Mastering the administration in connection with the experience of Iranian institutionalization.

Hezbollah has benefited from its deep ties with Iranian institutions,

whether the Revolutionary Guards, the civil services, or even the hawza

in Qom, to draw inspiration from the experience of building institutions

and organizing administration, which is one of the historical

characteristics of the Iranian experience.

A number of the institutions of the Islamic Revolution either initially

opened branches in Lebanon and then were run by the party, or

transferred their experience to the party, which copied it with a local

flavor and peculiarities.

Iranian experts in management and human resources have transferred

knowledge, skills, and administrative systems to party cadres that

worked to build and develop active and efficient civil institutions in

the fields of education, development, party organization, health,

services, and local administration.

The party's institutions usually benefit from Arab and Lebanese experts

and academics from outside its environment to gain access to qualitative

experiences and new knowledge.

The above-mentioned party institutions in the capital and the outskirts

attracted thousands of young men and women graduates of universities who

chose these majors or who were encouraged by the party to study in them

to benefit from modern sciences in management and human resources.

This institutional momentum contributes to the efficiency of the party's

activities and its ability to meet its needs, to preserve and transfer

experience, to development, to attract energies, and to adapt to

transformations, especially since the “Israeli” enemy has repeatedly

targeted these institutions.

13- Building strategic interests with Syria after years of mutual anxiety.

The relationship between the party and Syria was characterized by

mistrust and suspicion at the beginning, with several field frictions

between the two parties taking place, which reinforced the mutual

distrust.

Damascus aspired to gain the regulating position of the Lebanese reality

with international and regional recognition and to employ this in

Syria's internal stability, regional influence, and balance with the

“Israeli” enemy.

Some Syrian government officials were apprehensive that the party's

agenda, identity, and relationship with Iran could disrupt their

Lebanese project.

But with the war on Iraq, after Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the

failure of the Arab-“Israeli” settlement project, the end of the

Iraqi-Iranian war, and Hezbollah’s steadfastness in the face of the

“Israeli” enemy in the 1993 aggression, a new path was launched, the

beginning of which was to prevent President Hafez al-Assad, at the

initiative of the then commander of the Lebanese army, Emile Lahoud,

using the army to clash with the resistance in 1993.

Since then, it can be said that a door for direct communication opened

on the issue of resistance between the party and President al-Assad,

regardless of the complexities of the so-called Syrian-Lebanese security

system.

This relationship was strengthened during the “Israeli” aggression in

1996 when Syria played a key role in the birth of the April

Understanding.

The relations between the two parties were strengthened after the

American invasion of Iraq and Resolution 1559, as Syria realized its

need for the party and its necessity regionally and in Lebanon.

Syria also became a vital strategic depth for the party with the

expansion of the confrontation arena after 2011, which was proven by the

party’s entry into the war in Syria in 2013.

The party succeeded in understanding Syria’s concerns in Lebanon and

kept pace with its vital interests by not clashing with the post-Taif

regime and revealed to it its weight in the conflict with the “Israeli”

enemy. The strategic partnership that developed over time between Syria

and Iran helped in this.

14- The awakening of the marginalized Arab Shiites.

With its rise, the party became the center of the Shiites' eyes, hearts,

and minds in the Arab world. They have experienced decades of exclusion

and abuse, similar to the Zaydis in Yemen.

Thus, they

found in the successes of the Shiite Hezbollah a possible entry point

for Islamic and national recognition. This oppression of the Arab

Shiites served as an amplifier for Hezbollah's achievements and a

motivator for being identified with it and drawing inspiration from it.

Thus, Hezbollah's regional influence is primarily a product of its soft

power, a power characterized by long-term results and acceptable costs.

It is a fully legitimate influence.

The party supports the choice of these Shiites in peaceful struggle,

encourages climates of dialogue with their partners and the governments

of their countries, emphasizes Islamic unity, respects their national

privacy, helps them in the media to raise their voice to demand rights,

and urges them to political, media, and popular participation in support

of the resistance project within the region.

15- Healing the Arab psychological defeat through victory over

the “Israeli” enemy and support for the rising resistance project in

Palestine.

A large part of Arab societies took pride in Hezbollah's resistance,

interacting with it and getting closer to it, as they found it a

response to decades of disappointment and defeats.

Hezbollah has been keen to highlight its Arab identity in its political,

cultural, and media discourse and in its artistic products (anasheed)

and has strengthened its institutions concerned with communicating and

engaging in dialogue with Arab elites, parties, and groups.

This Arab fascination with the party's experience in fighting the

“Israeli” enemy and in its leadership constituted a provocative factor

for the Arab official regimes that emerged from the conflict with the

enemy, as the party's successes practically undermined the discourses of

complacency and the legitimacy of its advocates.

This explains the insistence of a number of regional regimes on creating

sectarian tensions that have had negative repercussions on the party's

relationship with part of its Arab incubators.

But the decline of the sectarian wave as the party continues to lead

Arab resistance efforts against the “Israeli” entity can create

conciliatory atmospheres with Arab incubators on the basis of

understanding and dialogue, organizing differences, and neutralizing

them from the resistance project.

16- Inspiration, representation, and transfer of experience

Hezbollah has limited material, human, and financial resources.

Therefore, its building of partnerships and alliances at the regional

level within the resistance project had to be based on its most

prominent assets, namely its ability to inspire and transfer its

experience and lessons learned to its peers within movements and forces

that practice the act of resistance.

What made this possible was that the party’s victories revived the

spirit of resistance in the Arab and Islamic spheres (for example, the

comparison between Sayyed Nasrallah and President Abdel Nasser abounded)

and thus stimulated the desire of many groups and elites to understand

and benefit from the party’s experience.

The most prominent results of this appeared in occupied Palestine, especially in the second intifada.

Therefore, Hezbollah was interested in transferring its experience in

resistance, administration, media, and organization to a large network

of Arab and Islamic non-governmental political actors involved,

militarily or politically, in confronting the American hegemony system.

The transfer of experience naturally includes the transfer of values,

ideas, patterns of behavior and practical culture, as well as

establishing networks of links and relations with the cadres of these

movements and parties.

Thus, over time, additional groups joined the equations of force and

deterrence for the resistance project. The Zionists started talking

about multiple circles of the resistance axis that extend to Iraq and

Yemen.

By Housam Matar | Al-Akhbar Newspaper

Translated by Al-Ahed News

/129